Filmmakers have long sought to protect their works from unauthorized alteration and modification. Practices such as colorization, pan and scan, lexiconning (the speeding up of motion pictures for broadcasting purposes), and re-editing are rare today due to a combination of enlightened and progressive legislation and high-profile campaigning by noted filmmakers.

Internationally, the moral rights of authors1 are protected by the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works of 1886, administered by the World Intellectual Property Oganization (WIPO) and signed by 167 countries. The integrity of artistic works is protected under Article 6bis (Second Instance of Article 6) of the Convention:

(1) Independently of the author’s economic rights, and even after the transfer of the said rights, the author shall have the right to claim authorship of the work and to object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, the said work, which would be prejudicial to his honor or reputation.

United States law refers to the concept of “material alteration”, initially defined in Section 11(a)(5) of the National Film Preservation Act of 1988 and dealing with colorization and “other fundamental post-production changes”. This concept is developed in more detail in Section 2, Paragraph 5 (I) of the Film Disclosure Act of 1995 (Page 10, Lines 12 thru 19), which amended the Lanham Trademark Act of 1946, inserting new clauses into Section 43.

Paragraph 5(I) and sub-clauses (i) and (ii) of the additions state:

(I) the terms ‘materially alter’ and ‘material alteration’—

(i) refer to any change made to a motion picture;

(ii) include, but are not limited to, the processes of colorization, lexiconning, time compression or expansion, panning and scanning, and editing;

These concepts – of “distortion, mutilation” or other modification as cited in the Berne Convention and of “material alteration” in U.S. law – remain relevant and applicable to current new technologies.

In this context, the contemporary practice of re-issuing only reductive, digital video-based binary versions of restored motion pictures to circumvent the creation of new photochemical projection prints raises serious ethical and legal issues. Without the consent of the authors of motion pictures (as defined in the Berne Convention and above acts), it is legitimate to assert that such practices can constitute prima facie “material alteration”, “distortion”, or other modification of these artistic works, as defined.

The issue is not the making of digital video-based copies of motion picture materials per se. This is a legitimate extension of practices that have existed for several decades, from the earliest telecine methods to current scanning technologies. The crux of the matter is the exclusivity involved. Converting a film to digital-only format is a greater degree of alteration than making editorial changes or inserting new shots: such alteration removes the ability of both filmmakers and audiences to experience a filmed motion picture in its original format.

Enlightened enhancement of the existing legislation could uphold the rights of artists working in the motion picture field and guarantee choice in how their works are exhibited and preserved. Furthermore, it could strengthen the emerging area of audience rights and give voice to a constituency completely ignored during the recent discourse on cinema exhibition technologies and practices.

Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works

National Film Preservation Act of 1988 (a constituent of Public Law 100-446—Sept. 27, 1988: An act making appropriations for the Department of the Interior and related agencies for fiscal year ending September 30, 1989, and for other purposes)

Film Disclosure Act of 1995 (HR 1248, Page 10, Lines 12 thru 19)

Lanham Trademark Act of 1946 (15 USC 1125 – July 5, 1946: An act to provide for the registration and protection of trademarks used in commerce, to carry out the provisions of certain international conventions, and for other purposes)

- The artistic, academic, and cultural impact of an increasingly non-print-based exhibition paradigm has been discussed in some depth in recent years. We cite some perceptive work on the topic in the Recommended Reading section of the Resources area on the AMIA Film Advocacy Task Force website.

- The ethical aspects of the use of recent intermediate digital technologies in motion picture restoration have been considered by experts in the field2 as these, too, are open to inappropriate usage.

1. In the United States, studios and production companies are considered authors of filmed work

2. E.g. The Moving Image (Spring 2007, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 78-91), Wallmüller, Julia, Criteria for the Use of Digital Technology in Moving Image Restoration

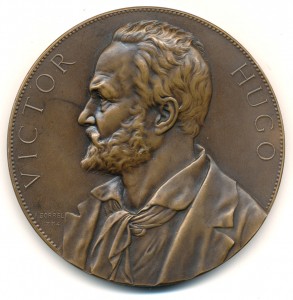

Image: Médaille à l’effigie de Victor Hugo, œuvre de A. Borrel, 1884, Bronze, 68mm by Defranoux is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

(Victor Hugo, L’Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale and the Berne Convention)